Disaster, as conventionally referenced by many federal agencies or relief groups, is defined by a quantifiable amount of damage to the environment – both natural as well as constructed – and injury to human life. However, that period of destruction undoubtedly evokes a human response, which can be generalized as a phase consisting of responsive growth and rapid development. Disaster, in fact, begets this growth and social unification through which a group of people are able to renew their attitudes toward the environment and the local community. This revitalization may be physically manifested in the rebuilding of houses, but may more importantly be demonstrated psychologically and emotionally through the reconstruction of homes.

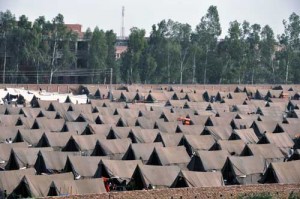

Perhaps, this regeneration can be classified into the categories as aforementioned – a tangible transformation that represents a more immediate response as well as an abstract one that is a reflection of the emotional impact of the disaster. An example of the immediate, physical response is the makeshift shelters that are erected following the destruction of homes (fig. 1).

There is a period of immense productivity and activity when relief workers and those affected by the disaster work to provide these temporary housing units. An example that demonstrates the presence of renewal in such a reaction is the development of new construction strategies that include the community and simplifies the construction process so that participation is all-inclusive and fosters a deeper sense of unity (fig. 2).

Disaster can act as an external motivator to unification of the people, and becomes generative from a social perspective. Even in fast and seemingly impersonal relief efforts, there is an overarching sentiment and a shared, recognizable need for renewal and community (fig. 3).

As time distances the actual disaster event, the notion of productivity may find other outlets, such as in a variety of art forms or even through cultural events (fig. 4).