In the introduction to “Project Japan: Metabolism Talks”, there was a pair of groupings that caught my attention. The first of these was a group of three powers: bureacracy, business, and media. The second of these was a group of vulnerabilities, specifically the lack of space, the consistent presence of natural disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis, and the difficulties of incorporating technology in a systematic manner. As propounded by Kawazoe, “we regard human society as a vital process… the reason why we use such a biological word, metabolism, is that we believe design and technology should be a denotation of human vitality.” I interpret this statement, along with the manner in which the vulnerabilities were addressed by specific projects, to be a comprehensive portrayal of the justifications of those respective project concepts.

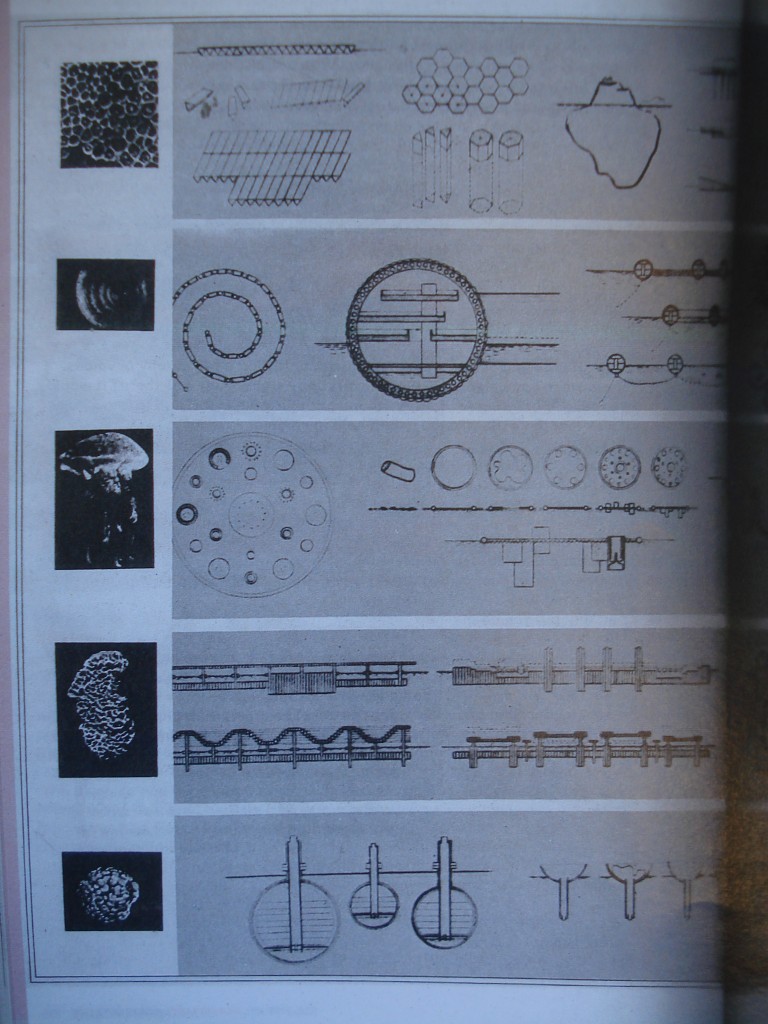

I was particularly taken by the Floating Cities as proposed by Kikutake. The first set of diagrams in the following image presents a floating surface that achieves its buoyancy through its aggregates as it extends into the ocean, and its figural form from the water lily. Such projects treat the natural boundary between land and sea with an organic attitude; it seems not so much about the earth invading the water but more so about embracing the sea with the manmade structure. In more abstract terms, the project transforms a recognized vulnerability into a unique, conscientious solution.

Many of Kikutake’s propositions include the use of smaller units to create a larger composite, which is also reflected in Maki’s concept, “Group Form”. This part-to-whole relationship is reflected in natural landscape of Japan, and also presents a different perspective to view the layers of infrastructure within the nation. Group Form capitalizes on an interdependence that begets form, contrary to a form that is critically and intentionally designed. If this idea is, similarly, taken to its abstract hierarchy, then the notion of Group Form is a healthy acknowledgment of the bureaucracy between those small parts and a proposition to address the unification of the small, individual archipelagos composing Japan to form a larger architecture.