This week’s work is an incredibly touching series of individual experiences, responses, statements, stories, and reflections. Deeply personal and often hopeful, these messages offer an interesting link for those connected to tsunami, both locally and from a distance.

One of the most powerful components of this work for me was the use of single words as titles: Relief, Pajamas, Overwhelmed, OK. Each of these titles actually convey a message in themselves.

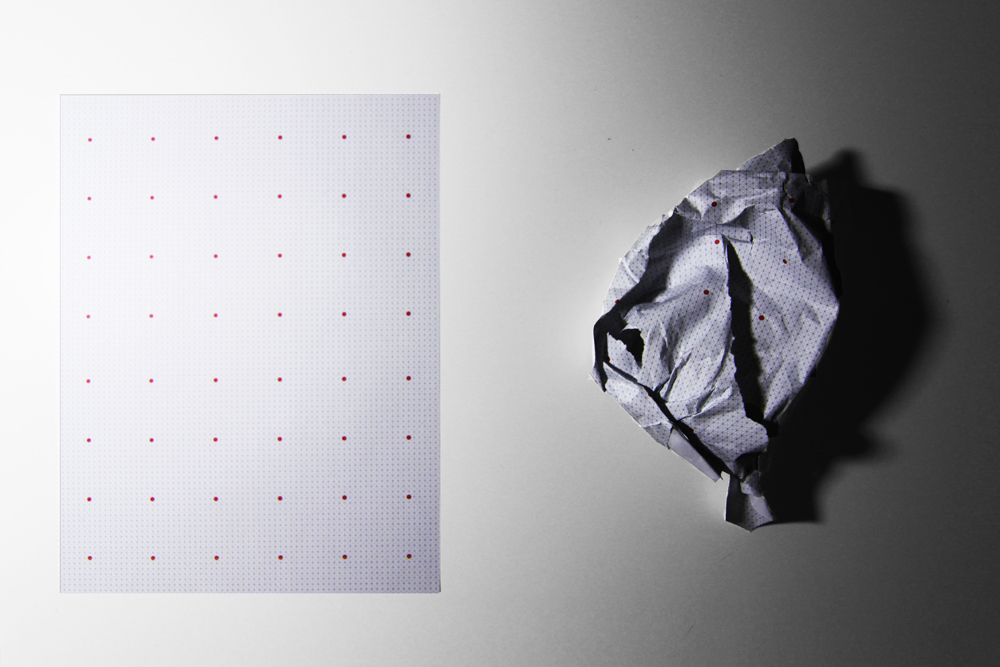

When I relate this to the question of the work I hope to do with the children in Japan and Afghanistan, I feel that my word is “voice”, but to concisely convey this to the children will be difficult. Given the language and translation challenges, and my hope to connect children visually rather than through language, I wonder how this same power can be conveyed through images. A single word comes with a host of connotations and impacts, but a picture, as they say, is worth a thousand words. Can the same coherence be offered through children’s images that are often filled with much more content and imagination than they seem to at first glance?