Flying Paper (Tayara Warakiya) is a documentary film that tells the uplifting story of resilient Palestinian youth in the Gaza Strip on a quest to shatter the Guinness World Record for the most kites ever flown.

Children in disasters around the world are understood to be one of the most vulnerable segments of the population. Many of us are vaguely, if not deeply, aware of the current situation in Afghanistan, and approximately half of Afghanistan’s population is made up of children, and they are considered to be some of the most at-risk children in the world. Continued war and violence has led to increased exposure to the elements, and limited access to social services, leaving the children of Afghanistan vulnerable to innumerable hazards. Most recently, this has left children living in camps exposed to the harsh winter. Coupled with malnutrition, the impact of the cold has been exacerbated, and the death toll of this protracted war has risen once again.

Young children in particular are vulnerable to the legacy that the war has left – Afghanistan has one of the highest mortality rates in the world for children under five years old. Of the over 450,000 internally displaced people, more than 54 per cent are children. Landmines continue to be a problem; only 27 percent of areas with landmines have been cleared. Particularly tragic, many mines were embedded in toys in order to target children specifically who would be drawn to the toy. In this environment, it is heartbreaking, but unsurprising to learn that on average, two children per day die in Afghanistan as a result of the ongoing conflict.

These statistics and the documentary only give half the story: while there are incredible challenges that these children face, there is something more there; something that can be learned from these children. Like children around the world, those in Afghanistan are aware of their surroundings and understand the challenges that they face. However, my experience with these children as refugees in Canada, Pakistan and in their home communities in Afghanistan over the last thirteen years has taught me a great deal about their strength in the face of conflict and disaster. It lies in their ability to hope. Whether it is turning a muddy hill into a slide or putting on a painted mask, in the midst of the challenge of being born during a time of war, the children of Afghanistan have been able to find joy and comfort.

This ability is not unique to children in Afghanistan. Indeed, in Japan in the wake of the 3/11 disaster, it seems the same is true. The potential for hope is everywhere.

On January 17th 1995, one of the most infamous Japan earthquakes was happened in Kobe and left 6,425 dead, 25,000 injured and 300,000 displaced. And, it caused a demolition of 100,000 buildings.[1] This earthquake could be considered as a latest disaster in Japan which could be compared with Tohoku earthquake in terms of scale of damage. As the numbers indicate, it caused not only a great number of casualties but also a multitude of broken artifacts.

In post-disaster situation, people in this area have to deal with a great burden of debris to reconstruct the town. It almost took 3 years and 3.2 billion dollars just to clean up the remnants of massive edifices before new construction.[2] As the following chart shows, the volume of debris too big to be easily eradicated.

Table 1. Debris Quantities in Past Events

|

Year |

Event |

Debris Volume |

Data Source |

|

2011 |

Tohoku earthquake |

25 mill tones |

(Yomiuri, 2011)[2] |

|

2008 |

Sichuan earthquake |

20 mill tones |

(Taylor, 2008)[3] |

|

1999 |

Marmara earthquake |

13 mill tones |

(Baycan, 2004)[4] |

|

1995 |

Hanshin-Awaji earthquake |

14.5 mill tones |

(Yomiuri, 2011)[2] |

Not only the debris volume per se but also this chart indicates two more critical crises in post-disaster Japan. Firstly, we have to consider about the gross volume of destruction in Japan. Since this country is located in unstable geographic zone, the Circum-Pacific orogeny, it has been suffered by numbers of frequent earthquakes. And, those result as an excessive volume of debris. But the eradication process of this artificial debris is not sustainable in terms of capacity of nature’s self-purification. Thus the constant collection of debris due to the continuous earthquakes in the country is creating more desperate situation for Japan.

On top of it, we also have to think about a growing physical volume of artificial structures in cities. Since a building technology has been advanced and economic growth has been made, the growing cities have been bulged with higher volume of artifacts than ever before. Consequently, the cities should have to face a bigger volumetric collapse.

In these regards, we could infer that sustainable way of processing debris in post-disaster situation is critical for Japan. Recent article about Tohoku area is already reporting that the reconstruction of this area facing great difficulty because of these excessive artificial detritus. [2]

Because of these reasons, I am getting more convinced with the concept of ‘deconstruction’. Deconstruction is a process of both decomposition and reorganization. It should be separated from the concept of destruction in terms of existence of reassembling. At the moment, our process of debris could be considered more of destruction, since we mostly just clear out the sites after the artifacts have been destroyed.

However, I want to input the notion of deconstruction into the process of debris. With this input of concept, we could possibly find out the better way for post-disaster reconstructions. And this following animation shows a figurative model for deconstruction process that I am conceiving.

Deconstruction:

From Decomposed Debris

to Reorganized Structure

[1] T.R. Reid. 1995. National Geographic. July. 1995.

[2] Yomiuri Shimbun. 2011. Mountains of debris overwhelm Japanese. 04. 17. 2011.

[3] Taylor, A. 2008. Sichuan’s earthquake, six months later. The Boston Globe.

[4] Baycan, F. 2004. Emergency Planning for Disaster Waste: A Proposal based on the experience of the Marmara. Earthquake in Turkey. Coventry. UK.

The worst disaster in Japan since the second world war hit the country’s north-east coastal region on 11 March 2011. The combination of tsunami and nuclear crisis presented the media with great practical problems and ethical concerns. Wataru Sawamura, an experienced journalist with the leading newspaper the Asahi Shimbun, reflects on how he and his colleagues sought to fulfil their professional responsibilities as the tragedy unfolded.

Full article in: Open Democracy, February 11, 2012

When a natural disaster strikes a nation, it leaves the nation’s people vulnerable to danger and uncertainty. These risks are not limited to just the physical wreckage, but also penetrates the political and psychological environment. The period of unrest and insecurity following a disaster is a dangerous one that has the potential to bring to the surface false notions and beliefs about who is to blame for the rising crisis.

The Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 in Japan is a prime example of how a political conflict and crisis can follow a natural disaster. As a result of the earthquake and tsunami, other incidents such as raging fires and poisoned water wells fell upon Japan’s Honshū region. (The following images are postcards that depict the fires that razed Japan’s cities.)

- Asakusa Nakamise Shopping Arcade Devoured by Flames

- Asakusa Park and Twelve Stories in Flames

- Aftermath of Great Kanto earthquake showing the fire near the Yamashita bridge in the Kyobashi district

- Aftermath of Great Kanto earthquake showing the licensed brothel district in Yoshiwara quarter burning

(More photos can be accessed here.)

Since these phenomena did not appear to be directly related to the earthquake, rumors accusing individual parties and factions of starting fires and poisoning the water started to spread. Since 1910, Korea was a colony under Japanese rule, and many Japanese civilians viewed the Koreans with suspicion of rebellion and revolution. These sentiments only fueled the rumors, and the realm of suspect also expanded to include the Chinese, Okinawans, and speakers of more local Japanese dialects.

The characters in the Japanese language, ga gi gu ge go (がぎぐげご) – though other sources may cite other ra ri ru re ro (らりるれろ) – were used as a shibboleth to identify the ethnicities of individuals.

Not only were outsiders targeted, but the vigilante violence also infiltrated Japan’s own politics. The nationalist government of Japan met opposition with unionists, socialists, and anarchists – advocates of “left-wing” thinking – and a number of radicals fell subject to the wave of civilian crime and fear.

As mentioned in a paper published by Clancey and Orihara:

“Print reactions began to extend their range beyond the traumatized and tragic, and the search for scientific explanations, to include the optimistic and even euphoric, the later condition being referred to in some disaster-studies writings as ‘post-disaster utopianism.’”

A question worth asking is, then, how far will the human condition allow such a witch hunt and a desperate, idealistic search for a resolution to go? Estimated death tolls as a result of the massacre reach up to 6,000, though the number reported by the government lies only in the hundreds.

It is interesting to consider how the after-effects of the earthquake garnered an overarching feeling of suspicion and ill-will toward a particular group of individuals, and why there existed such a need to identify and rectify a root cause. A parallel can be drawn in relating the massacres and series of crimes in 1923 to the 3/11 crisis in Japan, though in contemporary 2011, the conflict has arisen from the nuclear crisis. The victim – in some opinions, the scapegoat – is clear: Tokyo Electric Power Co. However, in targeting the utilities, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) also faces public criticism for failing to properly manage the entire situation, for hesitating in making crucial decisions, and for falling short in making amends. Consequently bureaucrats look for the return of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and while the political factions are reversed in this situation, there is still this growing conflict and underlying power struggle between two internal political groups in Japan.

Al Jazeera talks to Professor Toshitaka Katada, a Japanese disaster management specialist

>Full al Jazeera article by Donald Harding – November 23, 201

Disaster, as conventionally referenced by many federal agencies or relief groups, is defined by a quantifiable amount of damage to the environment – both natural as well as constructed – and injury to human life. However, that period of destruction undoubtedly evokes a human response, which can be generalized as a phase consisting of responsive growth and rapid development. Disaster, in fact, begets this growth and social unification through which a group of people are able to renew their attitudes toward the environment and the local community. This revitalization may be physically manifested in the rebuilding of houses, but may more importantly be demonstrated psychologically and emotionally through the reconstruction of homes.

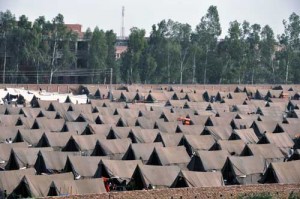

Perhaps, this regeneration can be classified into the categories as aforementioned – a tangible transformation that represents a more immediate response as well as an abstract one that is a reflection of the emotional impact of the disaster. An example of the immediate, physical response is the makeshift shelters that are erected following the destruction of homes (fig. 1).

There is a period of immense productivity and activity when relief workers and those affected by the disaster work to provide these temporary housing units. An example that demonstrates the presence of renewal in such a reaction is the development of new construction strategies that include the community and simplifies the construction process so that participation is all-inclusive and fosters a deeper sense of unity (fig. 2).

Disaster can act as an external motivator to unification of the people, and becomes generative from a social perspective. Even in fast and seemingly impersonal relief efforts, there is an overarching sentiment and a shared, recognizable need for renewal and community (fig. 3).

As time distances the actual disaster event, the notion of productivity may find other outlets, such as in a variety of art forms or even through cultural events (fig. 4).

From a young age, the word “disaster” never evoked images of our natural environment rising up against (or playing an integral role in) human settlements, livelihoods, and cultures. Having grown up in Vancouver, we had always heard about “the big one” that was coming – an earthquake which is expected to reach magnitudes beyond what has been experienced in Vancouver in recent memory. However, year after year, “the big one” never arrived, and resulted in a sense of false security that perhaps it never would, or that somehow the danger had been averted.

I grew up learning at the side of my parents – both trained as eye specialists who spent whatever time they could (often during our school holidays) in various parts of the world, training doctors and nurses, and providing eye care to some of the most marginalized communities in the world. These experiences from my early childhood alerted me keenly to the man-made disasters we see today: policies that failed to provide enough food for the population, schooling that limited human potential, and war and the many challenges that are associated with it. Nature did not enter the equation, in my mind at least.

It was not until the winter of 2005 that I realized the absolute reliance that we have on our natural environment. I was working in Khorog, Tajikistan, in the mountains of the Pamirs. One night, after a trip to Dushanbe, we were driving back to Khorog (a 14 hour drive), along treacherous mountain roads. As we drove, the roads behind us were closed by avalanches. Indeed, an avalanche fell just in front of our car about two hours from Khorog. We had the option to dig and continue driving, or spend the night in a nearby village to continue driving in the morning. We decided to pass, opting for getting home rather than imposing on a family for the night. After a great deal of effort, and several close calls with an almost continuous stream of avalanches onto the road, we arrived in Khorog.

The next morning we discovered that many of the surrounding villages were cut off from the rest of the country, and that would be the case for the next month. Food became scarce, homes were destroyed, lives were lost. This experience, was my first, and most immediate, realization of the true magnitude of natural disasters, particularly in mountainous regions.

Disaster is a failure of artifacts.

When natural disaster happens, artificial structures are retuned to default in terms of conventional intelligence of structural mechanics. Civilian casualties happen when these artifacts could not properly react to the stress of natural event. In perspective of nature, a concept of disaster per se could not be existed. For nature, every event is just part of its own cycle. A notion of disaster is only applicable in the human-made environment.

Disaster could be considered as a point that form and function of human-made objects meet the limitation.

Construction by human – Deconstruction by nature

Scrutinizing remainders after 3/11 Tsunami in Japan, residues of artifacts could be considered as seriously destructed. However, we could see this process as a deconstruction rather than a destruction. Jacques Derrida, a French philosopher, had written about the definition of deconstruction in his mail to his friend in Japan, “To deconstruct was also a structuralist gesture or in any case a gesture that assumed a certain need for the structuralist problematic. But it was also an antistructuralist gesture, and its fortune rests in part on this ambiguity. Structures were to be undone, decomposed, desedimented.”[1]

In this regards, we could consider disaster as a process of destruction of human artifices. Our conventional knowledge of structure has been critically dissolved by the nature for a recomposition.

1. Derrida, Jacques [1983] Letter to a Japanese Friend, in Wood, David and Bernasconi, Robert (eds., 1988) Derrida and Différance, Warwick: Parousia, 1985

Minami Sanriku: An Archeology of People and Place (an excerpt)

Interviews conducted by Jegan Vincent de Paul and Shun Kanda with the help of Sendai-based film maker and interpreter Takaharu Saito. This interview project is supported by a grant from the d‘Arbeloff Fund for Excellence in Education in collaboration with the Japan 3/11 Initiative.